Draconomicon: The Book of Dragons (2003)

Andy Collins et al., Draconomicon: The Book of Dragons (Renton, WA: Wizards of the Coast, Inc., 2003).

Hatching Dragon Eggs

When a dragon egg finishes incubating, the wyrmling inside must break out of the egg. If the parents are nearby, they often assist by gently tapping on the eggshell. Otherwise, the wyrmling must break out on its own, a process that usually takes no more than a minute or two once the wyrmling begins trying to escape the egg. All the eggs in a clutch hatch at about the same time.

Properly tended and incubated dragon eggs have practically a 100% hatching rate. Eggs that have been disturbed, and particularly eggs that have been removed from a nest and incubated artificially, may be much less likely to produce live wyrmlings.

Incubating Dragon Eggs

Once laid, a dragon egg requires suitable incubation conditions if it is to hatch. The embryonic wyrmling inside a dragon egg can survive under inadequate incubation conditions, but not for long. An embryonic wyrmling inside a dragon egg becomes sentient as it enters the final quarter of the incubation period. Dragon egg incubation conditions are as follows:

White: The egg must be buried in snow, encased in ice, or kept in a temperature below 0°F.

Wyrmling (Age 0-5 Years)

A wyrmling emerges from its egg fully formed and ready to face life. From the tip of its nose to the end of its tail, it is about twice as long as the egg that held it.

A newly hatched dragon emerges from its egg cramped and sodden. After about an hour, it is ready to fly, fight, and reason. It inherits a considerable body of practical knowledge from its parents, though such inherent knowledge often lies buried in the wyrmling’s memory, unnoticed and unused until it is needed.

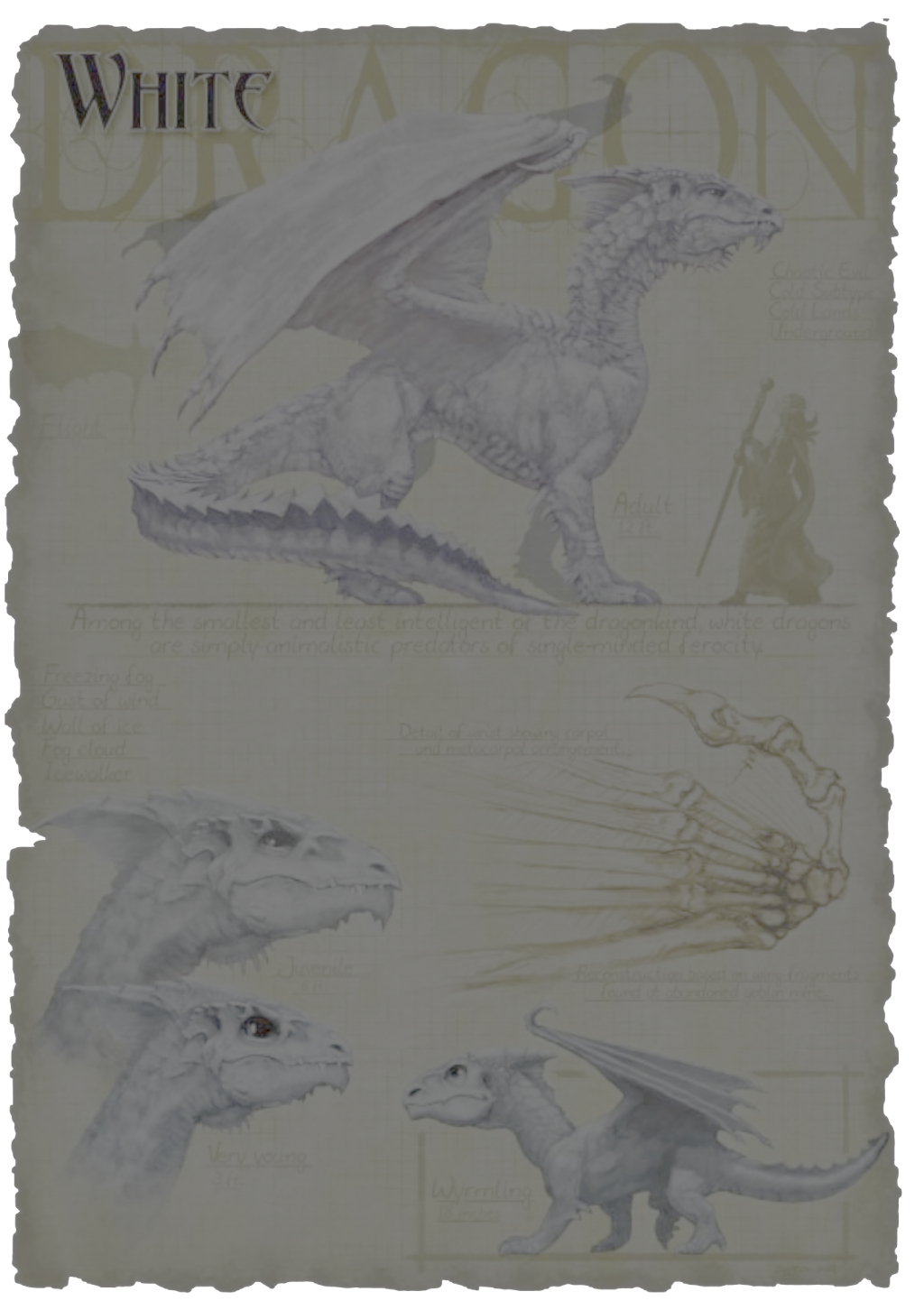

Compared to older dragons, a wyrmling seems a little awkward. Its head and feet seem slightly oversized, and its wings and tail are proportionately smaller than they are in adults.

If a parent is present at the wyrmling’s hatching, the youngster has a protector and will probably enjoy a secure existence for the first decades of its life. If not, the wyrmling faces a struggle for survival.

Whether raised by another dragon or left to fend for itself, the wyrmling’s first order of business is learning to be a dragon, which includes securing food, finding a lair, and understanding its own abilities (usually in that order).

A newly hatched wyrmling almost immediately searches for food. The first meal for a wyrmling left to fend for itself is often the shell from its egg. This practice not only assures the youngster a good dose of vital minerals, but also provides an alternative to attacking and consuming its nestmates. Wyrmlings reared by parents are often offered some tidbit that the variety favors. For example, copper dragons provide their offspring with monstrous centipedes or scorpions. In many cases this meal is in the form of living prey, and the wyrmling gets its first hunting lesson along with its first meal.

With its hunger satisfied, the wyrmling’s next task is securing a lair. The dragon looks for some hidden and defensible cave, nook, or cranny where it can rest, hide, and begin storing treasure. Even a wyrmling under the care of a parent finds a section of the parent’s lair to call its own.

Once it feels secure in its lair and reasonably sure of its food supply, the wyrmling settles down to hone its inherent abilities. It usually does so by testing itself in any way it can. It tussles with its nestmates, seeks out dangerous creatures to fight, and spends long hours in meditation. If a parent is present, the wyrmling receives instruction on draconic matters and the chance to accompany the parent during its daily activities. Wyrmlings on their own sometimes seek out older dragons of the same kind as mentors. Among good dragons, such relationships tend to be casual and often last for decades (a fairly short period by dragon standards). The youngster visits the older dragon periodically (monthly, perhaps weekly) for advice and information. Evil dragons, too, often counsel wyrmlings that are not their offspring—evil dragons lack any sense of altruism, but usually understand the role of youth in perpetuating the species. No matter what kinds of dragons are involved, such mentor-apprentice relationships require the younger dragon to show the utmost respect and deference to the older dragon, and to bring the mentor gifts of food, information, and treasure. Should the older dragon ever come to view the apprentice as a rival, the relationship ends immediately; when evil dragons are involved, the ending is often fatal for the younger dragon.

Rearing a Dragon

Being an adoptive parent to a dragon is no easy task. Even good-aligned dragons have a sense of superiority and an innate yearning for freedom. Most dragons instinctively defer to older dragons of the same kind, but they tend to regard other creatures with some disdain.

Older and wiser dragons eventually learn to respect non-dragons for their abilities and accomplishments, but a newly hatched wyrmling tends to regard a nondragon foster parent as a captor—or at best as a well-meaning fool. Still, it is possible for a nondragon character to forge a bond with a newly hatched wyrmling.

Dragons and Languages

All dragons speak Draconic. With their high degree of intelligence, most dragons have an affinity for language and speak additional languages as well. Many even study the science of language, developing a wide range of tongues.

About White Dragons

The smallest, least intelligent, and most animalistic of the true dragons, white dragons prefer frigid climes—usually arctic areas, but sometimes very high mountains, especially in winter. Mountain-dwelling white dragons sometimes have conflicts with red dragons living nearby, but the whites are wise enough to avoid the more powerful red dragons. Red dragons tend to consider white dragons unworthy opponents and usually are content to let a white dragon neighbor skulk out of sight (and out of mind).

White dragons’ lairs are usually icy caves and deep subterranean chambers that open away from the warming rays of the sun. Dungeon-dwelling white dragons prefer cool areas and often lurk near water, where they can hide and hunt.

A white dragon’s face expresses a hunter’s intense and single-minded ferocity. A white dragon’s head has a sleek profile, with a small, sharp beak at the nose and a pointed chin. A crest supported by a single backward-curving spine tops the head. The dragon also has scaled cheeks, spiny dewlaps, and a few protruding teeth when its mouth is closed.

When viewed from below, a white dragon shows a short neck and a featureless head. Its wings appear blunted at the tips. The trailing edge of the wing shows a pink or blue tinge, and the back edge of the wing membrane joins the body near the back leg, at about mid-thigh.

The scales of a wyrmling white dragon glisten pure white. As the dragon ages, the sheen disappears, and by very old age, scales of pale blue and light gray are mixed in with the white.

A white dragon will consume only food that has been frozen. Usually a white dragon devours a creature killed by its breath weapon while the carcass is still stiff and frigid. It buries other kills in snowbanks within or near its lair until they are suitably frozen. Finding such a larder is a good indication that a white dragon lives nearby.

White dragons love the cold sheen and sparkle of ice, and they favor treasure with similar qualities, particularly diamonds.

White dragons spurn the society of others of their kind, except for members of the opposite sex. They are prone to carnal pleasures and often mate just for the fun of it. They seldom tend their eggs, but they often lay their eggs near their lairs, and one or both parents allow the youngsters to move in for a time. The offspring are expected to care for themselves, but they gain some measure of protection and education from having their parents nearby.

It would be a mistake to consider a white dragon a stupid creature. Older white dragons are at least as intelligent as humans, and even younger ones are much smarter than predatory animals. Though not known for their foresight, white dragons prove cunning when hunting or defending their lairs and territories. White dragons know all the best ambush spots for miles around their lairs, and they are clever enough to pick out targets and concentrate attacks until one foe falls, then move on to the next foe. White dragons prefer sudden assaults, swooping down from aloft or bursting from beneath water, snow, or ice. They loose their breath weapons, then try to knock out a single opponent with a follow-up attack.

Although they are not pillars of intellect, white dragons have good memories, especially for events they have witnessed or experienced directly. They remember any slight or defeat and have been known to conduct malicious vendettas against beings or groups that have offended them.